Most of your landings will be normal and in the center of the drop zone, but unusual things do happen like landing in water, in sudden high winds, descending through power lines or trees.

Turbulence

As mentioned earlier, bumpy air may be encountered at any altitude and it has been known to close end cells and upset canopies. Jumpers have been robbed of their wings to be left back in freefall at 75 feet. Bumpy air may occur on windy days and on hot, no-wind days. Keep your canopy inflated during turbulence by flying at one-quarter to one-half brakes and make gentle turns. If turbulence causes a partial canopy collapse of your canopy, bring the steering lines down to half to

three-quarters brakes to help the canopy to reinflate.

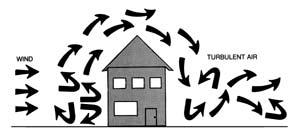

Turbulence near the ground may be caused when wind flows over obstacles such as buildings and tree lines. Avoid landing on the downwind side of any obstacle. The air may be bumpy or descending. The stronger the wind, the farther downwind the turbulence will exist and the taller the object, the higher the turbulence will be. Turbulence can be significant downwind as far as twenty times the object’s height. For a fifty-foot tree line, that could mean 1,000 feet downwind turbulence.

Turbulence also occurs behind other ram-air canopies. Stay away from the area directly behind another canopy about 45 degrees up from the trailing edge.

Dust Devils

Dust devils are very dangerous. They can rob you of your canopy when you need it most — near the ground. Look for the spinning dust clouds. Unfortunately they can’t be seen over grass.

One jumper landed, his canopy deflated and then it was reinflated by a dust devil. The swirling wind picked him up and then threw him back on the ground. He died from the impact. In windy conditions, pick up your deflated canopy immediately. In bad conditions, stand on it.

High winds. If you find yourself in high winds, look behind you as you back up. Many jumpers back into power lines and fences. When landing in high winds, let go of one toggle as soon as your toes touch the ground. Keep the other toggle at the flare position and quickly pivot 180 degrees in the direction of the depressed toggle. Steer the canopy into the ground. Run toward and around it to collapse it. If necessary, continue pulling on that toggle and reel in its line to pull the canopy out from under itself.

Once you are on your feet, stand on the canopy and remove your harness. Don’t let it reinflate and start dragging you all over again.

Thunderstorms

Thunderstorms are violent vertical lifting of air masses, a phenomenon which can build cumulonimbus clouds from near the ground to anywhere from 50,000 to 75,000 feet. Thunderstorms possess violent updrafts and downdrafts along with lightning. While the West Coast of the U.S. has only around five thunderstorms each year, the northeast has 20, and Florida 80 to 90. Jumpers have been caught in cumulonimbus clouds for some pretty scary and wet rides. When the storm clouds appear, put the gear away.

The Tree Landing

The tree landing is rarely hazardous if you “center” the tree. Your canopy will lower you gently into and through the trees as you slow further, breaking the thinner branches. You will probably go all the way through to the ground and make a normal parachute-landing fall on

the other hand, if you clip a tree with a wing tip, your canopy may collasp, dropping you to the ground.

If you can’t avoid the trees, face into the wind to minimize your ground speed, pull half brakes, and place your feet and knees tightly together so you won’t straddle a branch. Do not attempt to brake your descent by grasping limbs; you are better off going all the way through to the ground slowly than ending up sitting in the top of the tree. Prepare for a PLF. If you come to rest short of the ground, check your position. Students should wait for DZ personnel to come to their aid.

If your feet are within three feet (1m) of the ground, unfasten your chest strap and then your (solid saddle) leg straps and drop to the ground. If you do not undo the chest strap first, you could injure your neck as you fall away.

If you are up quite a way, relax and wait for help. If help does not arrive, you may have to climb down. Perhaps you are way off the DZ and dusk is approaching. It’s hard to shout continually, and it is nice to have a whistle in times like these. You may deploy the reserve canopy without activating the cut away mechanism (for S.O.S. type equipment, pull the metal cable out of its housing without disturbing the plastic-coated breakaway cables), let down the canopy and lines and then climb down hand over hand. If you let the narrow lines slip through your fingers and aren’t wearing gloves, you will receive painful friction

burns, so go hand over hand.

Keep your helmet on until you have both feet firmly on the ground. Its purpose is to protect your head from takeoff to touchdown, and you aren’t down yet.

Power Lines

You must avoid power lines at all cost; the danger is just too great. Look for the high-tension wires. If you are at an unfamiliar DZ or land off target, look for poles; wires run between them invisibly. Keep power lines continually in mind from the time you open so you can avoid them. High-tension lines don’t look dangerous, but they strike with the speed and power of lightning. They may electrocute you in an instant or put you in the hospital with severe burns; it isn’t at all pleasant. If there is any question about clearing the lines, turn and run with the wind until you are past them and make the decision high enough. It will be better to land downwind than to land in power lines.

If landing in the wires is inevitable, it is essential that you avoid touching more than one wire at a time. Any bird will tell you that it takes touching two wires to get zapped. If you are going into the wires, face your canopy into the wind to minimize horizontal drift, pull half brakes to make your final descent as close to vertical as possible. Drop your ripcord or anything else in your hands. Place your feet and knees firmly together with the toes pointed to avoid straddling a wire. Look for wires and wriggle and squirm as necessary trying to avoid touching more than one at a time. If you come to rest near the ground, check below to see what is underneath you. If there is no hazard below you and it is less than five feet to the ground — and assuming it is the main canopy that is hanging you from the wires you might decide to execute a breakaway and get away from the danger area as quickly as possible, but it would be better to wait for calmer heads to give you guidance in this matter. If there is a hazard below you or if it is your reserve parachute that is hanging you from the wires, you must wait calmly for competent, professional help. Any movement on your part may force an electrical contact. If a local resident walks up desiring to help you, ask them to call the power company and the DZ in that order. Warn would-be rescuers not to touch you or your gear until the power has been turned off. They could complete a circuit between you and the ground with fatal results.

Once you get to the ground, be alert for broken power lines, they are like snakes hidden in the grass and they not only strike, they sometimes start fires. Never pull on a canopy attempting to remove it from the wires, it may be your very last good deed. Let the power company do it; it is their kind of work.

Water Landings

There are two types of water jumps — those you plan and those you don’t. An intentional water jump is an exciting, rewarding combination of aviation and water sports. But being unexpectedly blown out over a body of water is cause for great concern. In fact, while few jumpers have perished in a planned water jump, 48 perished in unexpected water landings between 1967 and 1984. These figures have dramatically decreased now that the use of ram-air canopies has become universal and floatation devices for operations within one mile of water are mandated by the BSRs.

The procedures for these two very different types of landings are not the same.

In an intentional water landing you will slide back in the saddle, undo the chest strap, the bellyband (if there is one), and loosen both leg straps slightly (unless you have a full saddle harness, in which case you can release one leg strap up high, then the last leg snap upon splashing down). This procedure is also recommended if you find yourself being blown unexpectedly out over the ocean or other immense body of water. When there is absolutely no question that you are going for a dunking, you should inflate your floatation device. Don’t get out of your gear until you get wet. Don’t break away when you think you are about to get wet. Depth perception over water is deceptive. You may think you’re at 20-feet, but you’re probably much higher. Without knowing how deep the water is, you almost guarantee yourself a landing injury if you don’t steer the canopy all the way to the surface. For landing purposes, assume the water is just a few inches deep. Take a deep breath and prepare to do a PLF. Line up your landing into the ground winds (you may have to use the sun’s position for a reference) and once you are wet, swim or work your way forward out of your gear. Don’t try to save the gear at first. Remember that it is replaceable, you aren’t. Worry about the gear later, when you are safely away from it. Better yet, let someone else (such as your water landing crew) worry about it.

When making an intentional water jump, conditions are good, the jump is planned and the necessary flotation equipment is worn. The ingredients for tragedy, on the other hand, are born by being unprepared for the unexpected.

The Basic Safety Requirements insist on carrying flotation gear when parachuting within one mile of any water deep enough to take a life, but there are times when one mile is not enough. A bad spot on a big load with high upper winds, sudden radical wind changes, or a popped round reserve as you exit at twelve grand, for examples, may carry you far from the friendly DZ. Some water requires more protection than just flotation gear, such as when a jumper punches through the ice in the wintertime.

Most unintentional water landings are also unexpected. They take place in narrow rivers and small ponds; so small that you don’t know you are going into them until just a short distance from splashdown. There is no time to do much water-landing preparation, particularly if you are trying to avoid trees. As a result, you are going into the water in all your gear and your chances are poor.

On the other hand, if you go through the intentional water landing procedure just in case and then miss the water only to land in the trees because you couldn’t spend enough time steering, you may subject yourself to other dangers.

The greatest danger in water landings is becoming entangled in the net-like canopy and lines. In fact, we should think of: panic-canopy-entanglement-drowning. All are challenges, very much related, and either of the first two can lead to the others. If there is little wind in the small tree-protected pond, the canopy will deflate and fall straight down on you in a huge mess of tangled nylon fabric and lines. If you panic, you are sure to become caught in the trap. It seems logical, then, to try to avoid the canopy, or better yet, avoid the water landing.

The procedure recommended for unintentional water landings is as follows: You are at 1,000 feet and the wind is backing you toward a water hazard. If you continue to face the wind, you may land short of it and if you turn to run, you may land on the other side of it, but one thing is for sure: you will land in the vicinity of it. So, take the action outlined below and then at double to triple the height of the trees, face into the wind to minimize your ground speed, pull your

toggles to half brakes, and place your feet and knees firmly together in preparation for a PLF.

Two Action System (TAS)

Continue to steer, activate your flotation gear if you have it, undo your chest strap and your belly band if there is one. Loosen your leg straps so that you can slide the saddle forward a bit. Disconnect the RSL. Then, just before touchdown, reach for the canopy release handle. At the moment your feet get wet, not one moment sooner, activate the releases. The tensioned canopy will recoil upwards and even a mild wind will carry it away. Altitude is very difficult to judge, especially over flat ground or a large body of water. One is always tempted to drop out of the harness just before touching down, but what appears to be just a leg length may really be building height, so don’t break away until your feet are in the water.This procedure will leave you floating with your harness and reserve on but with the dangerous unpacked main canopy gone. Roll over on your back and take off the harness. Actually, the harness won’t hurt or restrict you and the packed reserve will even provide positive flotation. In fact, the reserve won’t become negatively buoyant for about three minutes. So, you can use it for temporary flotation.

Single Operation System (S.O.S.). With the S.O.S. system, if you jettison the main canopy, the Stevens lanyard will activate the reserve. Allow yourself to get wet, bend forward and then swim or work your way forwards out of the loosened leg straps as quickly as possible. Get clear of the canopy.

If the canopy does land on top of you anyway, grab it and follow/walk a seam to the edge of the canopy. There is no reason to panic as you can always lift the porous fabric to form a space to breathe. Once clear of the canopy, swim away using mostly your hands until you are clear of the lines. Keep kicking to a minimum, as pumping legs tend to draw lines and fabric toward them.

If you should land in a river, even a slow moving one, you want to jettison your main as soon as possible. If it catches in the current it will drag you under and/or downstream away from your rescuers.

Besides your reserve, certain other pieces of your gear may provide some flotation. Pneumatic soled jump boots, full shell helmets, knotted jumpsuits, etc.; they are all there for those who think to use them.

You must undergo (dry) unintentional water-landing training for your USPA A license and (wet) live water training with full gear for the B license. These requirements have probably saved hundreds of lives so far.

Buildings

Landing on a building presents two distinct hazards. First, you might go through the roof of the building, which may lead to a broken or cut extremity. Second, if it is windy, you might find yourself being dragged off of the building and going for a second extremely hazardous landing. If you feel your life is in danger (such as being dragged off a high building), break away from the main as quickly as possible. Don’t worry about the reserve inflating — it won’t have enough of a

chance to do so. If it is your reserve that put you on the building, try to collapse it as quickly as possible. If that doesn’t work, you’re going off the building in the wrong position for a second landing and there probably won’t be much of a chance to get into a PLF mode, but try to anyway.

Other Obstacles

There are many other landing obstacles that are potentially hazardous to parachutists such as ditches, fences, hard roads and even some unique ones like hot water geysers. These hazards at your DZ will be pointed out to you in your first jump course, probably with a marked aerial photograph. When visiting a new drop zone, be sure to check in with an instructor or the Safety & Training Advisor for a briefing on their local hazards and recommended alternate landing areas.

When you are in the air, look for the danger areas. Invisible

barbed wire runs between visible fence posts, power lines run between power poles, isolated buildings are served by electricity. Power lines, ditches, and fences often border roads, airplanes land on runways, etc. This should all be obvious, but sometimes it’s not. It is all new to you and the view is different: you are looking down at the terrain now, not horizontally.

If an obstacle presents itself, steer your canopy to avoid it. Turn your canopy to run and land beyond it, if necessary. If you are going to strike an object, hit it feet-first. Successful landings under a parachute are like those in an airplane: the ones you walk away from are good. It is far better to land outside the target area and walk back than land on a fence and be carried back. Don’t let get home-itis get you. If you pass over the obstacle very low, you may not have sufficient altitude to turn into the wind for landing. It is then preferable to crab the canopy slightly and try to do your best forward PLF. But, obviously, the best solution is to think and plan ahead to avoid the obstacle in the first place. The most important rule about landing hazards is: Continually make efforts to avoid them. The second rule is: It is better to land flying downwind than to hit an obstacle.