Search the Community

Showing results for tags 'disciplines'.

Found 51 results

-

IntermediateBoth competitors participate exclusively in the orientation of Frontmonaut. Make-up of the 5 manches: Manche 1 : 3 [Free] Manche 2 : 3 [Free] Manche 3 : 2 [Free] + 1 [Block] Manche 4 : 3 [Free] Manche 5 : 2 [Free] + 1 [Block] For every manches there will be a draw of the individual moves for the respective and eventual sequence. Moves for the Category Intermediate

-

An unplanned water landing is a frightening scenario for many skydivers; it’s one of the reasons that live water training is required for a USPA B License (If you didn’t truly get wet when working on your USPA B license, your instructors weren’t doing you or anyone else any favors). Add a wingsuit to the mix and it’s enough to give pause to even the most experienced skydiver. In 2010 alone, we’ve had three known unintentional wingsuit water entries in the USA. Wingsuits can fly further than skydivers can, and water is an attractive hazard to fly-over. Toss in a low deployment, restricted movement, and some adrenaline and a normal skydive can get really exciting really fast. OK, so it’s not quite the same as Houdini and his locks, and skydiving in a “prom dress” or freefall in a straight jacket isn’t nearly as difficult as some make it out to be. However, emergency situations do require a different approach. Wingsuit skydivers should pre-plan for an unintentional water landing even if flight over water isn’t an issue at their home DZ. A boogie or other special event may put wingsuit pilots into unfamiliar situations where water is present. Flotation devices should be a part of that pre-planning process if over-water flights are a common occurrence. TSA allows for up to four Co2 cartridges to be carried as part of a "life-vest unit." USPA Training And Recommendarions Section 6.2 of the USPA Skydiver Instruction Manual (SIM) guidance for unintentional water landings tells us to: a. Continue to steer to avoid the water hazard. b. Activate the flotation device, if available. c. Disconnect the chest strap to facilitate getting out of the harness after landing in the water. d. Disconnect the reserve static line (if applicable) to reduce complications in case the main needs to be cut away after splashing down. e. Steer into the wind. f. Loosen the leg straps slightly to facilitate getting out of the harness after splashing down. (1) If you loosen the leg straps too much, you may not be able to reach the toggles. (2) Do not unfasten the leg straps until your feet are in the water. g. Prepare for a PLF, in case the water is shallow (it will be nearly impossible to determine the depth from above). h. Flare to half brakes at ten feet above the water (this may be difficult to judge, due to poor depth perception over the water). i. Enter the water with your lungs filled with air. j. After entering the water, throw your arms back and slide forward out of the harness. (1) Remain in the harness and attached to the canopy until actually in the water. (2) If cutting away (known deep water only), do so only after both feet contact the water. (3) If flotation gear is not used, separation from the equipment is essential. k. Dive deep and swim out from under the collapsed canopy. All of these same procedures apply when wearing a wingsuit, yet preparations for an unintentional water landing don’t stop there. We still got work to do. Prior To Entering The Water It goes without saying that the best way to avoid a water landing is to avoid being over the water. However, sometimes it cannot be avoided. In addition to the previously mentioned, USPA-recommended actions, the wingsuit should be unzipped as much as possible prior to landing. This includes armwings, legwings, and body zippers if possible. Do not pull the cutaway/release cables on the wingsuit (assuming the wingsuit has cutaway cables, not all do) if the arms can be unzipped. An armwing that has been cut away will be much more difficult to move and unzip once it has filled with water and your arms are still in the sleeves (For example, the newest Phoenix-fly wingsuit arms might be cut away, as they detach the full wing from the arm, but the arm will still be inside a foam sleeve making it difficult to swim). The tailwing may act as a drag point and force the upper body forward, putting the skydiver on his belly. Enter the water with feet and knees together. Flying at half brakes should allow the canopy to continue forward. Do not flare. Take a deep breath prior to entering the water. After Entering The Water The canopy is a potential point of entanglement. It is recommended that a main canopy be cut away once you are fully in the water. If there is a current, this will prevent the main from dragging you along with it. A reserve cannot be cut away without a hook knife (if you are going to carry a hook knife, carry a metal, not plastic hook knife. A $5.00 hook knife will not do the job). Roll backward or sideways onto your back. If you have not deployed the reserve, the reserve will keep you floating for approximately 30 minutes in fresh water, longer in saltwater. With the tail (and perhaps the armwings) potentially being still inflated, being on your back will prevent the tail and rig from forcing your face into the water. Try to remain calm, breathe deeply and begin the process of removing goggles, helmet, and legstraps (chest strap if it was not undone in the air). The arm and legwings of a three-wing style wingsuit are similar to a ram-air parachute; there is an inlet and air fills the cells. These same inlets and cells can fill with water as easily as they fill with air. Although water in the cells alone will not cause the wingsuit to sink, movement of the wing will cause the suit to be dragged downward. This means that attempting to tread water will drag you under. Do not attempt to tread water, but rather keep your legs motionless. If there is any current, it is imperative that you stay on your back and try to keep your head upstream. Keeping the legs apart will help achieve this goal. Even a slow current will move your body very fast. Remaining calm is perhaps the most important aspect of clearing the suit and surviving. Jeans, boots, and gloves can make the task of escape a little more difficult than expected. Once you are fully unzipped and your legstraps loose, slide your rig and armwings off. After the upper body has been freed, “sit down” in the rig and suit to put you head-high. This allows the torso to roll forward so that it’s possible to dive deep and away from the rig, allowing the legs to escape from the legstraps and tailwing. Although the USPA SIM instructs skydivers to swim away from their rig, I have made the personal choice that I will not swim away from my rig if the reserve has not been deployed. It may be used as a flotation device and might be the difference between life and death. I will cut away the main canopy and swim away from the main. This is my personal decision and is in opposition to USPA recommendations. Follow at your own risk. During the various water experiments, there were a total of 49 water entries in various conditions and wingsuits, all with a rig or dummy rig in place, many with a main canopy attached. Performance Designs Sabre II, Silhouette, and Storm canopies were used. We jumped into still water 18’ deep, 6’ deep, current pools 34” and 24” deep with speeds up to 7 knots. We also jumped into wave pools with swells of up to 3’, which are small to moderate compared to coastline swells. Tossing the main canopy into the 7 knot current pool. Summary During these entries, three things became clear; Go into the water with as many zippers undone as possible. Your chest strap should also be undone for best possible speed once in the water. while this may seem logical, in at least two of the three unintentional water landings, the wingsuiter forgot to unzip arms while dealing with other issues. Get onto your back as quickly as you can. Stay on your back as legstraps, zippers, helmet releases, and goggles are removed. You may want to consider leaving the helmet on if in moving water and head protection is needed. Take a deep, calming breath. Even though my experiments were intentional water landings, they were still nerve-wracking when the suits were fully zipped up. Being jittery is entirely likely. Staying calm and keeping heart and breathing rates down may easily be the difference in survival, particularly in cold water. Be sure to stay clear of the canopy and lines. Currents may drag the canopy around a bit. Rescuers might have an easier time finding you if they can spot the canopy in the water so staying somewhat near but well clear of canopy and lines is a good idea. A hook knife should be part of your kit. When landing in water that has a current, try to keep your head upstream while getting out of the suit. Leave the helmet on to protect your head from rocks and other objects. Stay as far away from the canopy as possible. This is easier said than done. Note that in the video, the current combined with the canopy drag was more than two men could manage even in shallow water. This is where a hook knife would be beneficial. If the rig has a reserve still packed in it, it will float. It also is very easy to escape once the legstraps are undone, as it will remain on top of the water as you dive forward away from the container. "Exiting" from the 3 meter board, fully zipped In conclusion, if over-water wingsuit flights are planned, seriously consider a floatation device. They will not have a significant impact on the comfort of the suit, and are not relatively expensive. ParaGear, ChutingStar, and other skydiving supply shops sell these devices. Remember that CO2 cartridges may not be carried aboard a commercial flight, so you’ll need to source or ship cartridges to your final destination. If a flotation device is not part of your gear/kit, have an advance plan in the event of a water landing. There have been at least three known unintentional water landings in the US this year; only through luck and calm procedures did the wingsuiters survive. Read the Incident Report below to see how one survivor described his experiences and how multiple errors led him into the water. Big puffies and blue skies (and calm waters, I suppose)! -d Douglas Spotted Eagle is a USPA AFFI, Coach Examiner, PRO, and PFC Senior Examiner (North America) on staff at Skydive Elsinore. Student’s Incident report: ##### Name [Deleted] My age: 31 Years in the sport: 4.5 yrs. # of skydives: 287 # of Wingsuit SD’s: 7 # of BASE: 70+ I recently purchased a new Phantom2 Pheonix fly wingsuit and was super eager to get in the air. I got to the DZ and got on the first available load which was a 10 minute call. On any typical skydive, an immediete 10 minute call upon arrival isn’t so bad, but setting up a wingsuit system quickly is not a great idea, but I did. Mistake #1: I forced myself to have to rush to get on a load to do a technical jump for no apparent reason. In the end, I don’t think my rushed preparation lead to the actual situation, but I guess my mind wasn’t where it should have been. I was the last to exit from 12,500?. I had a really great (mostly stable) flight, flying around some clouds. At pull time, like most jumps, I was out over the ocean. I took one last look at my wrist alti at 5K’. Based on my audibles 4000? warning, I’m guessing I was open between 3500?-3000?. Mistake #2: I shouldn’t have pulled that low with a WS on with my low experience level. Mistake #3: I have made 6 previous WS jumps. All more than 2.5 years ago. I did not physically or mentally dirt dive this jump before getting on the plane. After a stable pull (I felt), I immediatley opended with line twists. I’ve had line twist before with this canopy/harness (Sabre 1, 150; 9 cell/Infinity dom;1997) and was able to kick out of them in the past. This line twist began to accelerate instantly. I made 3-4 attempts to kick out of it, but with the restricted movement of my legs in the WS, and spinning horizontally around the canopy, it didn’t do much at all. Mistake #4: I was under too small of a canopy for a WS jump. My exit weight= 240lbs. Wind loading= 1.6. I should have been under a more docile (7 cell), or larger canopy. So, having no luck with my kick attemps, I chopped it. It took me a few seconds to locate my handles (one hand on each). In my haste, I did a “T-Rex” style cut-away. As soon as I saw my right riser clear, I let go of the handle and pulled the reserve (also “T-rex”). Obviously leading to my main still dragging off my left shoulder. Mistake #5: I was jumping a borrowed rig. Although I’ve had about 20 uneventful (other than line twist) jumps with this rig. I wasn’t really familiar with it. Mistake #6: Probably the biggest one. I DID NOT CLEAR MY CUT AWAY CABLE/HANDLE COMPLETELY! Mistake #7: This goes right along with the above…Pulling my reserve WAY TOO SOON! I think because of my slightly slower descent rate (caused by my main still being attached), and my reserve already fired, I felt the second set of risers bouncing around on my head and saw all the lines whipping in-front of my face. As the reserve was slowly coming to line stretch, the lines were beginning to entangle with my helmet (actually the camera on my helmet) Mistake #8: Wearing a camera on a “student” WS jump. With the lines still “somewhat” relaxed, I thought of dumping my helmet but instead I picked/brushed the lines off the camera, clearing them. A split second later, I felt the canopy pressurize and go to complete line stretch. Instantly, the reserve risers had forced my head completely forward, making my chin squeeze into my neck. I knew I had MAJOR line twists on my reserve now too. So now, I’m under one collapsed main still dragging off my left riser, and one tightly twisted up reserve to my right side, still fully zipped into my WS, and I’m getting choked from behind by the reserve risers and can’t lift my head to see any of it. I knew I wasn’t “falling” anymore and that the canopies were not entangled. I don’t know, but the reserve must have been “un-spinning” because the pressure was slowly coming off the back of my neck and the twist opened up enough to squeeze my head back through, behind the risers. Mistake #9: Not sure if I could have prevented this one. If my arms had been unzipped and out of the wings (which they weren’t) I may have been able to reach back during the reserve deployment, and guided the risers in-front of my head before pressurization. At this point, my first objective was to finally cut the main off so I could get completely out of my reserve line twists. The main was still being held on by 1cm of ripcord cable still in the three ring release closing loop. In any case…I was focused on getting that last tinny bit of rip cord out of the closing loop. I had “tunnel” vision on trying to pick at the centimeter of cord. There was too much tension on the riser so I couldn’t get it out. I was definitely not thinking clearly at that moment. ALL I had to do was find my cut-away handle floating behind me and pull it another 1/4 inch. In retrospect, the dragging main (acting like an anchor) may have kept my reserve from continuing to twist and spin me into the ground/water. I’m not sure if completely cutting away at that point would have been any better. Mistake #10: Had I been thinking clearly, I would have found my handle and finished the job of cutting away. At this point I stopped all attempts to correct anything. I saw that I was about 300 yards(?) of the beach, over the water at about 500-300?(?) up. I knew I was going for a swim. The swell was small (2-3?), but definitely was not flat and calm. In preparation for my mid day swim, I started unzipping everything…chest, arms, legs, chest strap. I then reached above the reserve line twist, grabbed the rear/right line set and did a “rear riser” turn towards the visibly shallower water over the reef. I don't know if that helped at all because I pretty much felt like I was under a round canopy with no directional control. I just knew I was drifting towards the reef now. Not knowing the shallowness above the reef gave me a second of pucker factor, but at this point I had not much control or time anyway. I then did a “backwards” PLF (obviously with no flare, toggles still stowed and twisted). I slammed the water pretty hard. Mistake #11: Although this is what saved me from serious impact, I landed in the water with a WS on….not good! While I was underwater, my wingsuit quickly turned into a tunasuit, but before I even had time to deal with the next hurdle……..I stood up. I was now standing 300 yards out in the surf, in 3 feet of water with both canopies attached and the WS on, all filled with water. I was getting dragged in-land with the swell a little bit, but had plenty of time to finally cut-away the main and completely step out of the WS. I saw all the scrambling of people on the shore. I was soon reached by a couple of skydivers and a rescue kayak. We loaded up the rig on to the kayak and swam back to shore. Mistake #12: I probably should have made my first priority to un-zip my wings. Although, at no point did I feel like they were restraining my movement (until I wanted to steer towards the reef). I guess I unzipped them right when I had a moment and thought it was totally needed. ####### Massive thanks to: Lake Elsinore Casino Tooele City Pool Raging Waters/SLC Skydive Elsinore Skydive Utah Performance Designs Rigging Innovations Teledyne Instruments Joey Allred, Aaron Hutmacher, Jose Calderon, Mannie Frances, Karl Dollmeyer, Scotty Burns, Chuck Blue, Jarno Cordia, Bence Pascu, Joe Turner, Frank Hinshaw, T.K. Hinshaw, Tom Deacon, Jim Crouch, Jack Guthrie, Scott Callantine, Jeanie Curtis, Mike Harlon, Chris Squires, Robert Pecnik, Jeff Donohue, and Andreea Olea.

- 3

-

- wingsuiting

- disciplines

-

See more

Tagged with:

-

Freeflying is a physically demanding sport (as are other disciplines in skydiving) and like any physical activity it is much easier to damage your body if you do not prepare your body properly. Stretching helps prepare your body for the physical activity it is about to go through, by offering some of the following benefits: Relaxes your body (which is always good in freeflying) Helps your coordination and allows for easier movement Gives you a greater range of motion Increases your body awareness Improves circulation so if you do damage your body it will repair quickerA lot of freeflyers seem to think stretching takes a long time and that it isn’t important. It is very important and if you plan on jumping for a long time then stretching is the way to allow you to keep on jumping as you get older. Stretching can take a long time but it can also be a short 10 minutes in the morning. The following is a short and basic stretching routine to help you prepare yourself in the morning. This doesn’t mean you should only do this in the morning when you go jumping, try to do this every morning, it only takes 10 minutes. Guidelines for stretchingIf you do not stretch right you can damage your body just as bad as if you do not stretch. Some people think that stretching should be painful, this is wrong. You should feel comfortable in your stretch, feeling a mild tension in the area that your are stretching. You should never bounce into a stretch, take your time, and ease into it until you feel the mild tension mentioned earlier. Stretching routineYou should try to do this routine every morning to get the best effect. Start off by making sure you are warm, a hot shower to warm you up in the morning can help. Start by lying on your back, keeping your spine flat to the floor and look up at the ceiling/sky with your head. Start with one leg, bend it at the knee and pull it towards your chest until you feel a mild tension. Hold this position for 20 seconds and then move onto the other leg, taking a 10 second rest in between. [Figure 1] Next, lay on your back, keeping everything straight and looking up at the ceiling with your head. Bend your legs, keeping your feet flat on the floor. Place your hands behind your head and lift it up until you feel a tension in the back of your neck, still keeping the rest of your back on the floor. Hold this tension position for 5 seconds and then slowly lower your head back to the floor. Repeat this 3 times. [Figure 2] This is a good one if you have bad landings and find you hurt your ankles every now and then. Sit on the floor and have one leg flat. Grab the other leg just above the ankle. Rotate your foot clockwise providing a slight resistance with your other hand. Repeat this 20 times and then do the same but rotating your foot anti clockwise. Do not rush this. Now do the same with your other leg, again making sure you do not rush yourself. [Figure 3] Start by leaning against a wall with your head resting on your hands. One leg should be closer to the wall and bent with the foot facing straight forward. The other leg should be straight and behind you, foot facing the wall and the heel touching the floor. Slowly push your hips forwards, keeping your back straight, stop when you feel a mild tension in your calf. Hold this position for 30 seconds and then slowly move your hips back and relax. Repeat with the other leg, again taking your time. [Figure 4] Start by standing up straight with your feet shoulder width apart and facing straight forward. Slowly start bending from the hips keeping your knees slightly bent at the same time. Relax your neck and arms, keep bending until you get a slight stretch in the back of your legs. Hold this for 20 seconds and then slowly move back up. [Figure 5] Start by standing with the side of your body next to a wall, put the palm of your hand closest to wall against it just a bit higher than your head. Now slowly and gently turn your body away from the wall until you feel a mild tension in your shoulder, You should be between one and two feet away from the wall at this point. Hold this position for 15 seconds and then slowly turn back and relax for a few seconds. Now repeat this with your other hand. [Figure 6] Start by sitting on the floor and put the soles of your feet together, hold onto your toes. Now start to gently pull your self forwards towards your feet. Make sure you are moving from your hips and not bending from your shoulders or back. To help try resting your elbows on your knees for stability, this will make it easier. Keep moving forwards until you feel a good stretch in your groin. Hold this position for 40 seconds and then slowly move back and relax. [Figure 7] Now you’ve finished the stretching routine make sure you wrap up warm to get the best effect. Do this every morning and you will see a marked improvement in your flexibility and you will be much more relaxed in the air. Louis Harwood is a freeflyer from the UK and jumps at Target Skysports, in Hibaldstow. He has competed for the last two years in the Artistic nationals, he has two silver and one gold medal in B catagory freefly, freestyle and skysurf. www.avalore.co.uk

-

Freeflying is the ability to fly your body in any position, in any direction, at any speed at any given time. This includes, but is not limited to, headdown, sit, stand, back, belly and any kind of flying you can imagine. There are no limits to freefly except those created in your own mind. Freeflying Safety Freeflying is exciting, new and so much fun. Safety must always be an issue. By maintaining a safe flying atmosphere you allow yourself to have more fun. Flying safely relates to the level of experience of those with whom you fly. The basics of freeflight can practiced in a safe atmosphere as long as the size of the flying group does not exceed the skill level of those individuals flying together. 2-ways are the best way to train your freeflying skills. Freeflying involves many different flying positions which relates to many different speeds ranging from 90-300 miles an hour. There is a logical progression to safe learning of freefly. It is best to first have an understanding of how to fly your body in slower flying positions before moving on to faster ones. Learning to control speed, direction and proximity at slow speeds increases awareness and reactions. These are the methods which keep everyone safe in the sky. As stated earlier, smaller groups are the safest way to fly. One-on-one flying is the safest way to experience flight with someone else. It allows flyers to maintain visual contact with each other at all times. As experience increases and awareness grows, flying with more people can be fun and safe. This is dependent on the skill of the fliers and how well everyone has planned their dive. There are certain safety rules for breakoff. Once again speed is an important factor. Breakoff altitudes are slightly higher for freefly jumps, 4000ft because of higher speeds. It is also important to gently transition into a track to avoid radical changes in speed. Track for clean air and check. A slow barrel roll before deployment is highly recommended to insure clean air. Following the simple rules of small groups, planning, awareness and breakoffs, insures safety and fun for everyone. Freefly Safety Equipment Container: A tight fitting container which does not allow for exposure of risers and pins is essential to every freeflyer. Increased airspeeds and varying body positions make closure necessary. Altimeter: Two altimeters, visual and audible, are necessary for freeflying. Altitude awareness takes on a new importance when dealing with the faster speeds of freefly. Clothing: It is important to wear clothing that does not restrict movement and will not cover any handles. Helmet: A hard shell helmet is recommended. Cypres: Cypres is recommended to all those who can afford it. The potential for collisions exists. Therefore, it is best to be prepared.

-

1. AUTHORITYThe competition will be conducted under the authority granted by the Atmonauti Committee of the Sports Skydivers Association. All participants accept these rules and regulations as binding by registering as a competitor for the competition. 2. DEFINITIONS2.1 Atmonauti Body Position Atmonauti is the term given to the technique that intentionally utilises the torso (as an aerofoil) to generate lift, while ‘diving’ at an angle of between 30deg – 75deg to generate relative wind required for lift. Use of the torso to achieve lift allows freedom of limbs to achieve a range of handgrips and foot docks, essential for the ARW2 and SFIDA competition formats. 2.2 Atmonauti Relative Work 2.2.1 Sequences and Blocks, including transitions and inters, to include Frontmonauti, Backmonauti and Footmonauti positions. 2.2.1.1 Frontmonauti: Head first into relative wind, torso to earth 2.2.1.2 Backmonauti: Head first into relative wind, back to earth 2.2.1.3 Footmonauti: Feet first into relative wind, back to earth 2.3 SFIDA “Challenge” Neutral Navigator sets direction, angle and speed, Competitors compete side by side of the Navigator and aim to score highest points for that jump by virtue of preset docks and grips, to include transitions. 2.4 Team An Atmonauti Relative Work Team will consist of two (2) competitors and a videographer. For SFIDA no team will exist and two (2) competitors will compete against each other navigated by an appointed qualified navigator. The Videographer will be independent from the competitors. Grip and docks 2.4.1 Grip: a recognisable stationary contact of the hand or hands of one competitor on a specified part of the body or harness of the other competitor, executed in a controlled manner. 2.4.2 Dock: A recognisable stationary contact of the foot or feet of the one competitor on a specified part of the body or harness of the other competitor, executed in a controlled manner. 2.5 Heading The direction in which the “leading edge” of the performer faces. further defined in terms of Backmonauti and Frontmonauti positions 2.6 Leading edge A specific body part of the performer (either head or feet) which is the first point of contact with the relative wind generated from the angle of attack 2.6.1 Frontmonauti: Head first into relative wind, torso to earth 2.6.2 Backmonauti: Head first into relative wind, back to earth 2.6.3 Footmonauti: Feet first into relative wind, back to earth 2.7 Axis 2.7.1 3 axis – F (flight direction), P (Perpendicular to F) & H (Horizontal) 2.8 Atmonauti position Objective is to achieve head-on relative wind (or a custom “tube”) at an angle of between 30deg – 75deg to the ground, with horizontal movement in relation to the ground, whilst searching for lift with the torso - freeing up the limbs to achieve hand grips and foot docks. 2.9 Move A change in body position, and/or a rotation around one or more of the three body axes or a static pose. 2.10 Navigator Neutral Navigator responsible for setting direction, angle and speed. No eye contact or assistance should be present. 2.11 No Fly Zone Frontmonauti<.p> Behind, below, and not on head level during the approach (i.e. must be above, ahead and on head level). 2.12 No Fly Zone Backmonauti Ahead, above, and not on head level during the approach (i.e. must be below, behind and on head level). 2.13 Head level The level of the approaches - utilising the head as reference in relation to the angle of attack set by Navigator. 2.14 Total Separation Is when all competitors show at one point in time that they have released all their grips and no part of their arms or body have contact with another body. 2.15 Inter Is an intermediate requirement within a block sequence which must be performed as depicted in the dive pool. 2.16 Sequence Is a series of random formations/free moves and block sequences which are designated to be performed on a specific jump. 2.17 Scoring move/formation Is a move which is correctly completed and clearly presented either as a free move or within a block sequence as depicted in the dive pool, and which, apart from the first move after exit, must be preceded by a correctly completed and clearly presented total separation or inter, as appropriate 2.18 Infringement2.18.1 An incorrect or incomplete formation which is followed within working time by either 2.18.1.1 Total separation or, 2.18.1.2 An inter, whether correct or not. 2.18.2 A correctly completed formation preceded by an incorrect inter or incorrect total separation 2.18.3 A formation, inter, or total separation not clearly presented 2.18.4 In SFIDA, where one or both competitors cause instability to the navigator, adversely affecting the other competitor on the same jump. 2.19 Omission 2.19.1 A formation or inter missing from the draw sequence 2.19.2 No clear intent to build the correct formation or inter is seen and another formation or inter is presented and there is an advantage to the team resulting from the substitution. 2.20 Working Time Is the period of time during which teams are scored on a jump which starts the first moment and competitor (other than the videographer) separates from the aircraft, as determined by the Judges and terminates a number of seconds later as specified in chapter 3. 2.21 NV Moves, inters, or total separations not visible on screen due to meteorological conditions, or factors relating to the videographer's freefall video equipment that cannot be controlled. 2.22 Rounds Minimum 1 round to call the meet. 2.23 Backmonauti The performer will be on heading flying on his back with his back towards the earth. 2.24 Frontmonauti The performer will be on heading flying at the defined angle as per atmonauti definition with his back towards the sky. 2.25 Footmonauti The performer will be on heading feet-first flying at the defined angle as per atmonauti definition with his back towards the ground. 2.26 Formation A record attempt formation is considered as built when two or more competitors fly on heading with a predefined dock or grip held for minimum 3 seconds, and is the basis for the Atmonauti Linked National/World Records. A free move formation, however, is merely a recognisable stationary contact of the hand/hands or foot/feet – and does not require to be held for 3 seconds as per record attempts. 3. ROUTINES3.1 The discipline is comprised of SFIDA and Atmonauti Relative Work. 3.2 Number of rounds: a. SFIDA: a total of 4 competition rounds will be completed with a minimum of one round to be completed before a meet can be called. b. ARW: a total of 5 competition rounds will be completed with a minimum of one round to be completed before a meet can be called. 3.3 All SFIDA competitions will be judged by an elimination process where the two highest scoring competitors in any given round will compete against each other in the following round and the second and third ranking competitors will compete against each other and so forth. 3.4 In the case of a tie for a specific round, the previous total points are added to identify the highest total average per competitor. 3.5 Should a tie persist, a one jump tie breaker will be performed with the highest scoring competitor moving to the next round. 3.6 A tie breaker may also be required for placing 1st, 2nd, 3rd. 4. THE EVENTS4.1 The discipline will be comprised of the following events: 4.1.1 ARW Events: Exit altitude is 11 000 feet AGL; working time is 40 seconds. 4.1.2 SFIDA Events: Exit altitude is 11 000 feet AGL; working time is 40 seconds. 4.1.3 For meteorological reasons only, and with the consent of both the Event and Chief Judge, the Meet Director might change the exit altitude and/or working time and continue the competition. In this case the following conditions will apply: 4.1.3.1 The working time will be: a. 20 or 40 seconds for the ARW Events b. 20 or 40 seconds for the SFIDA Events. The reduced working time must be used if the exit altitude is lowered (ref 4.1.1 and 4.1.2). The next round must commence if working time is changed and all competitors will be scored on the same working time for a specific round. 4.1.3.2 The minimum exit altitude will be: a. 7 000 feet AGL for the ARW Events b. 7 000 feet AGL for the SFIDA Events. The maximum exit altitude will be 13 000 feet AGL for all events. 4.2 Objective of the Event 4.2.1 The objective of the event is for the a team (ARW) or single competitor (SFIDA) to complete as many scoring moves as possible within the given working time, while correctly following the sequence for the specific round. 4.2.2 The accumulated total of all rounds completed is used to determine the placing of teams for ARW and the process of elimination as defined in chapter 3 is applied to determine the placing of individual SFIDA competitors. 4.2.2.1 For ARW if two or more teams have equal scores the following order of procedures will be applied: 4.2.2.1.1 For determining final standings: a. the highest score in any completed round; b. the highest score starting with the last completed round and continuing in reverse order, round by round until the tie is broken, c. the fastest time (measured to hundredths of a second) to the last common scoring move in the last completed round. d. one tie break round if possible (for the first three placings only). 4.3 Performance Requirements 4.3.1 Each round consists of a sequence of formations depicted in the dive pools of the appropriate annexes, as determined by the draw.4.3.2 It is the responsibility of the team or individual competitor to clearly present the start of working time, correct scoring moves, inters and total separation to the judges. 4.3.3 Scoring moves need not to be perfectly symmetrical, but they must be performed in a controlled manner. Mirror images of moves and whole block sequences are not permitted. 4.3.4 In sequences, total separation is required between block sequences, between free or random moves, and between block sequences and free moves. 4.3.5 Where degrees are shown (180, 270, 360, 540) this indicates the approximate degrees and direction of turn required to complete the inter as intended. The degrees shown are approximately that amount of the circumference of the subgroup's centre point to be presented to the centre point(s) of the other subgroup(s). For judging purposes, the approximate degrees and direction of turn of subgroups centrepoints will be assessed using only the two dimensional video evidence as presented. 4.3.6 Contact or grips are allowed between subgroups during execution of the inter. 4.3.7 Where subgroups are shown, they must remain intact as a subgroup with only the depicted grips. 4.3.8 Assisting handholds on other jumpers or their equipment within a subgroup/competitor or a scoring formation are permitted. 5. GENERAL RULES5.1 Teams may consist of competitors of either or both sexes, except in the female event where (except for the videographer) all competitors must be female. 5.2 The Draw 5.2.1 The draw of the sequences will be supervised by the Chief Judge. Teams will be given not less than two hours knowledge of the results of the draw before the competition starts. 5.2.2 Event Draws: All the «Block sequences» (numerically numbered) and the «Free moves» (alphabetically marked) shown in the appropriate annex will be singularly placed in one container. Individual withdrawal from the container, (without replacement) will determine the sequences to be jumped in each round. Each round will be drawn so as to consist of three or four scoring formations, whichever number is reached first. Alternatively this draw can be done on a Recognised electronic scoring/judging system as approved by the Meet Director and Chief Judge. 5.2.3 Use of Dive Pool: Each block or formation will be drawn only once for the scheduled rounds of each competition. In the event that additional rounds are necessary, due to the tie-breaking jump-off, the dive pool for this round will consist of the blocks and free moves which were not drawn for the scheduled rounds. In the event that all of the remaining blocks and formations do not complete the tie breaking round, the draw will continue from an entire original dive pool in that event, excluding any blocks or formations which have already been drawn for that round. 5.3 Competitors are not allowed to use a wind tunnel (freefall simulator) after the draw has been made. 5.4 Jump Order 5.4.1 Determined by a draw. 5.4.2 Should conditions or availability not allow for Jump Order to be executed as per draw, Competitors ready and present shall be given first option to continue with the rounds. 5.5 Video Transmission and Recording 5.5.1 Each team shall provide the video evidence required to judge each round. Each freefall Videographer must use the video transmission system if provided by the Organiser. 5.5.2 For the purpose of these rules, «freefall video equipment» shall consist of the complete video system(s) used to record the video evidence of the team’s freefall performance, including the camera(s), video media, tape recorder(s), and battery(ies). All freefall video equipment must be able to deliver a PAL digital signal through an IEEE 1395 compatible connection (Firewire) or composite video compatible connection. 5.5.3 As soon as possible after each jump is completed, the freefall videographer must deliver the freefall video equipment (including the tape(s) used to record that jump) for dubbing at the designated dubbing station. 5.5.4 Only one video recording will be dubbed and judged. Secondary video recordings may only be used in NV situations. 5.5.5 The dubbing station will be as close to the landing area as possible. 5.5.6 A Video Controller will be appointed by the Chief Judge prior to the start of the Judges’ Conference. The Video Controller may inspect a team’s freefall video equipment to verify that it meets the performance requirements as determined by him/her. Inspections may be made at any time during the competition which do not interfere with a team’s performance, as determined by the Event Judge. If any freefall video equipment does not meet the performance requirements as determined by the Video Controller, this equipment will be deemed to be unusable for the competition. 5.5.7 A Video Review Panel will be established prior to the start of the official training jumps, consisting of the Chief Judge, the President of the Jury, and the Chairman, or acting Chairman, of the Atmonauti SSA Committee. Decisions rendered by the Video Review Panel shall be final and shall not be subject to protest or review by the Jury. 5.5.8 If the Video Review Panel determines that the freefall video equipment has been deliberately tampered with, the team will receive no points for all competition rounds involved with this tampering. 5.6 Exit Procedure 5.6.1 Exit first (prior to FS, AE, Wingsuiting on the same jump run) at altitude. There are no limitations on the exit other than those imposed by the JM for safety reasons. 5.6.2 The exit will be controlled by the Navigator in SFIDA and Team Principle in ARW2. Exit commands will be made using an appropriate signal system, and should be discussed prior to boarding with the pilot. 5.6.3 Atmo groups will be required to fly minimum 45 degrees off jump run in order to create horizontal separation to freefall groups exiting after atmonauti group. 5.7 Scoring 5.7.1 A team will score one point for each scoring move performed in the sequence within the allotted Working Time of each round. Teams may continue scoring by continually repeating the sequence. 5.7.2 For each omission two points will be deducted. If both the inter and the second move in a block sequence are omitted, this will be considered as only one omission. 5.7.3 If an infringement in the scoring move of a block sequence is carried into the inter (ref. 2.8), this will be considered as one infringement only, provided that the intent of the inter requirements for the next formation is clearly presented and no other infringement occurs in the inter. 5.7.4 The minimum score for any round is zero points, except where zero points have been awarded and penalty/ies imposed. 5.8 Rejumps 5.8.1 In a NV situation, the video evidence will be considered insufficient for judging purposes, and the Video Review Panel will assess the conditions and circumstances surrounding that occurrence. In this case a rejump will be given unless the Video Review Panel determines that there has been an intentional abuse of the rules by the team, in which case no rejump will be granted and the team’s score for that jump will be zero. 5.8.2 Contact or other means of interference between competitors in a team and/or their Videographer shall not be grounds for the team to request a rejump with regards to ARW. In the case of the SFIDA category adverse whether conditions such as bad visibility (in cloud), any contact or other means of interference between the navigator and competitiors and/or between the Videographer shall be grounds for the individual competitors to request a rejump – granted at the sole discretion of the Atmonauti Event Judge. 5.8.3 Adverse weather conditions during a jump are no grounds for protest. However, a rejump may be granted due to adverse weather conditions, at the discretion of the Chief Judge. 5.8.4 Problems with a competitor’s equipment (excluding freefall video equipment) shall not be grounds for the team to request a rejump. 5.9 Training Jumps 5.9.1 Each team in each event will be given the option of one official training jump before the draw is made. 5.9.2 The aircraft type and configuration, plus the judging and scoring systems to be used in the competition will be used for the official training jump. 5.9.3 Two sequences will be created by the Chief Judge. Only teams performing one of these sequences will receive an evaluation and posted score. 6. JUDGING 6.1 The official training jump and competition jumps will be judged as the Videographer provides the video evidence. The Chief Judge may modify this procedure with the consent of the FAI Controller. 6.2 The judging will, as far as practical circumstances allow (landings out, rejumps etc), be judged in the reverse order of placing. 6.3 Three Judges must evaluate each team’s performance. 6.4 The Judges will watch the video evidence of each jump to a maximum of three times at normal speed. If, after the viewings are completed, and within fifteen seconds of the knowledge of the result, the Chief Judge, Event Judge or any Judge on the panel considers that an absolutely incorrect assessment has occurred, the Chief Judge or Event Judge will direct that only that part(s) of the jump in question be reviewed. If the review results in a unanimous decision by the Judges on the part(s) of the performance in question, the score for the jump will be adjusted accordingly. Only one review is permitted for each jump. 6.5 The Judges will use the electronic scoring system to record their evaluation of the performance. At the end of working time, freeze frame will be applied on each viewing, based on the timing taken from the first viewing only. The Judges may correct their evaluation record after the jump has been judged. Corrections to the evaluation record can only be made before the Chief Judge signs the score sheet. All individual Judge’s evaluation will be published. 6.6 A majority of Judges must agree in the evaluation in order to; • credit the scoring move, or • assign an omission, or • determine an NV situation. 6.7 The chronometer will be operated by the Judges or by a person(s) appointed by the Chief Judge, and will be started as determined in 2.13. If Judges cannot determine the start of the working time, the following procedure will be followed. Working time will start as the videographer separates from the aircraft and a penalty equal to 20% (rounded down) of the score for that jump will be deducted from the score for that jump. 7. RULES SPECIFIC TO THE COMPETITION 7.1 Title of the Competition: Atmonauti National/World/Continental Championships 7.2 Aims of Atmonauti National/World/Continental Championships 7.2.1 To determine National/World/Continental Champions of Atmonauti in the: • ARW (Atmo Relative Work), • SFIDA “Challenge” 7.2.2 and • To determine the world standings of the competing teams, • To establish Atmonauti formation/distance/other world records, • To promote and develop Atmonauti, • To present a visually attractive image of the competition jumps and standings (scores) for competitors, spectators and media, • To exchange ideas, experience, knowledge and information, and strengthen friendly relations between the sport parachutists, judges, and support personnel of all nations, • To improve judging methods and practices. 7.3 Composition of Delegations: 7.3.1 Each delegation may be comprised of: • One (1) Head of Delegation, • One (1) Team Manager, • Freefall videographers as.7.3.4 and 7.3.2 At a World/Continental Championship: • Two (2) ARW2 teams consisting of up to: Six (6) ARW2 Competitors • One (1) female ARW2 team consisting of up to: Three (3) female ARW2 Competitors • SFIDA contestants consisting of up to: Three (3) Individual Competitors 7.3.3 At a World Cup: • Any number of teams per event (composed as for a World Championship) to be decided by the Organiser and announced in the bulletins. 7.3.4 Videographers must be entered for each team as part of the delegation and must be a member of the Delegation’s NAC. A Videographer may be replaced at any time during the competition, (with the agreement of the FAI Controller). The evaluation process for the video evidence will be the same for any Videographer. Videographers may be one of the following: a. One person in addition to the team composition in 7.3.2. This competitor is to be considered as a team member for the purposes of awards and medals. b. Any other person (ref 7.3.6). This Videographer is eligible to receive awards and medals. This Videographer may jump as a ‘pool’ Videographer and is subject to the same regulations as other competitors on the team. 7.3.5 If any ARW team consists of competitors from the SFIDA, they should be listed separately on the entry form. 7.3.6 Any ARW competitor can only enter in one ARW team as ‘performer’ but may enter as a ‘pool’ Videographer. A competitor in the ARW event cannot also enter in the Female ARW event. 7.4 Program of Events for SFIDA: 7.4.1 The World Championships is comprised of: • Up to 8 rounds considered as selection rounds, and • Final rounds, consisting of 4 quarter finals, two semi finals, one runners up and one finals round. 7.4.2 Time must be reserved before the end of competition to allow for the completion of the semi-final, final and runners up round. 7.4.2.1. The quarter-final rounds will consist of the individuals with the 8 highest scores from the selection rounds. 7.4.2.2. The semi final rounds will consist of the individuals with the 4 highest scores from the quarter-finals. 7.4.2.3. The finals round will consist of the individuals with the 2 highest scores from the semi final rounds. 7.4.2.4. The runners up round will consist of the lowest scores of each of the 2 semi finals rounds. 7.4.3 A selection round left incomplete must be completed as soon as possible, but after the round in progress has been completed. 7.4.4 If all the selection rounds are not completed at the starting time of the quarter-finals, the round in progress will become the semi final or final round as appropriate. Where this is the semi final, the next drawn round will be used for the final round. The following procedures will apply i) The round in progress will be completed if ten or less (in the case of semi finals) or six or less (in the case of finals) teams remain to jump. All scores for this round will count. ii) The round in progress will be performed by only the ten (in the case of semi finals) or six (in the case of finals) highest placed teams if more than ten (in the case of semi finals) or six (in the case of finals) teams remain to jump. The scores of any other teams in this round will be discarded. 7.4.5 The competition will be organised during a maximum time frame of 5 competition days. Exceptions may be made where a bid is received for multiple FCE competitions at one time. 7.5 Medals and Diplomas are awarded as follows: • All team members (ARW) and individuals (SFIDA) in the events will be awarded medals if placed First, Second or Third. • Certificates are awarded to all competitors that are placed First to Tenth. 8. DEFINITIONS OF SYMBOLS 8.1 Coding in the Dive Pool annexes is as follows: 8.1.1 Indicates Move by the competitor: See image 1 top right. 8.1.2 Indicates transition on “defined’ axis by competitor in either direction: See image 2 top right. 8.2 Visualisation for dock/grip positions, (Ref: 2.5) See image 3 top right. See image 4 top right.

-

Both competitors participate exclusively in the orientation of 'Fronmonaut" and "Backmonaut". Make-up of the 5 manches: Manche 1 : 3 [Free] Manche 2 : 2 [Free] + 1 [Block] Manche 3 : 1 [Free] + 2 [Block] Manche 4 : 3 [Free] Manche 5 : 2 [Free] + 1 [Block] For every manches there will be a draw of the individual moves for the respective and eventual sequence.

-

Both competitors participate exclusively in the orientation of "Frontmonaut" and "Backmonaut". Make-up of the 5 manches: Manche 1 : 3 [Free] Manche 2 : 2 [Free] + 1 [Block] Manche 3 : 3 [Free] + 2 [Block] Manche 4 : 3 [Free] Manche 5 : 3 [Free] + 1 [Block] For every manches there will be a draw of the individual moves for the respective and eventual sequence. Moves for the category Advanced

-

The SensationsSpeed skydiving in principle sounds like a high-octane, extreme discipline in skydiving. However, when you hear it’s a solo sport, you then think it “sounds boring”. But it is anything but boring and it’s for one simple reason; speed skydiving has a unique adrenaline-filled freefall sensation. It feels like those first few seconds of normal freefall where you accelerate rapidly, but throughout the entire speed skydive. Speed skydiving is measured as an average over the vertical kilometer (from 8,858 to 5,577ft). That means if you do it well, you can expect to reach your peak speed at the bottom end of the measuring gate. Some skydivers say it is hard to quantify what normal terminal velocity is, however in speed skydiving it’s definitely more tangible. The sensation is of freefalling seriously fast and that’s slightly scary whilst giving you a big adrenaline rush! Who Am I?I jump regularly at Skydive Hibaldstow primarily doing FS team camera work and wingsuiting. Although I have never been on the International Speed Skydiving circuit or a speed skydiving training camp, I always try to attend the UK Speed Skydiving Nationals and seminars. I’m not a freeflyer and I’m not even the best speed skydiver, but I have been enjoying it for 9 years. Doing It WellDoing it well is another matter of course. I have never done an average of over 270mph, whereas Mark Calland (UK jumper) has been over 300mph unbelievably. Speed skydiving requires you to strike a 3-way balance between feeling the airflow on your body, making fine corrections and relaxing. Putting too much input in or being too ridged and it’s all going to go pear-shaped. What to wear plays big part of getting a good average. Some speed skydivers like to wear bright red all-PVC spray on gimp-suits. Sorry but that is too kinky for me! If you can handle them, you can get some good speeds. Many more however prefer to wear a surfers rash vest and some jeans. The jeans help to smooth the airflow, provide some good stability and grip. A Typical Speed SkydiveSo let me describe a typical speed skydive. I get out of the aircraft between 12,000 to 13,000ft (the same altitude as the 8-way jumpers at nationals) and for the first 15 seconds, I slowly start to build up my speed by going into a progressively steeper and steeper track. After what feels like a long time, I begin to feel the air on the back of my calves. This is when I know I am now in the vertical airflow phase of the jump. Around this point, I feel a sudden acceleration and I know I am passing the 200mph mark. It’s almost like I’m passing through a pressure wave and this is common amongst other speed skydivers. For extra speed, I try to flatten my arms by my hips and bring my ankles together. Not long after, I pass through the opening gate of the measured kilometer. By then, I am already doing over 230mph. At this measuring phase of the jump, I’m concentrating on stability with every nerve cell in my body. Ideally, I’m trying not to make any inputs in at all. In fact, I’m trying to relax whilst balancing on what feels like a pinhead. Another sensation is like falling through an invisible narrow tube barely wide enough for my shoulders. I’m talking a lot about sensations in this article, but that is one of the big attractions to the discipline. Being symmetrical is also very important. A slight hip twist, one leg in front of the other and I can expect radical oscillations. Simply relaxing often cures the problem and I can continue to job of accelerating away. The final and most important part of the speed skydive is the deceleration to 120mph! I do this when I hear my two L&B; audibles beeping away inside my Oxygn fullface helmet. For those that don’t know, I’m completely deaf in one ear. So I pack them next to each other. You wouldn’t want to miss your beeps at those speeds. Pulling out of a 250mph swoop is not as gruesome as it sounds. You simply arch your body slightly and you begin to peel out into a swoop. As the speed decreases, you then bring your arms in front of you to a normal flat body position. All this takes less than 4 seconds and this makes you realise how fast you were actually going. MeasurementOnce you land, you unclip the two L&B; Pro-Tracks (not the ones from your helmet) from you harness lateral straps and plug them into the Jump Track software, which produces neat and tidy graphs showing your performance. In competition, each competitor does 6 rounds and the average of their best 3 go forwards. It’s exciting watching the scores come in and seeing your own progression. You would be surprised that being a fatty has little to do with going fast. I’m on the slim side and 2 out of the 5 worlds fastest recorded times have been by other slim built skydivers. SafetyHaving a premature opening of your parachute over 200mph is extremely dangerous. In preparation for a speed skydive, I take a fresh closing loop and shorten it to the point where I can only just get the closing pin in. In addition, I make sure I have two audibles in my helmet and I put gaffer tape on the edges of the visor of my full face. There should be no more than three speed skydivers on a load to prevent traffic problems. The first and last part of the jump involve tracking and it’s possible to cover large distances quickly. Being able to keep a heading is vital. The last thing is that your BOC spandex must be in good condition. SummaryThere are very few disciplines where you can feel how fast you are going and that makes it a real adrenaline buzz. Whilst it is a solo discipline, there is a lot of excited interaction and camaraderie between the jumpers at competitions as they evaluate each other’s jumps and acceleration graphs. You can take part without having to do lots of coached training camps. It’s definitely not boring! Doesn’t covering a vertical kilometer in less than 10 seconds sound like fun? More information: 1. Speed skydiving seminar at Hibaldstow 2. ISSA 3. Larsen & Brusgaard – Kind sponsors of the discipline

-

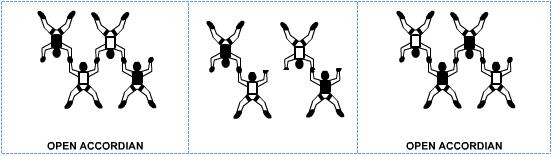

(This article was first published in the August 2004 issue of Parachutist as “One Good Turn Deserves Another”. Since then, the article has been updated and improved.) Turning a piece on a formation skydive is not as simple as yanking it around and hoping it will stop where it is supposed to. Jumpers in the piece must help it stay close and level throughout the turn, and they must help their piece partners start and stop the turn without rotating it too far or slamming it into the other piece. A piece that is yanked around too fast can rotate too far or even injure somebody. A piece that is not completely turned or turned incorrectly can drift away and actually become harder to control. This article shows the correct (and safe) techniques for turning pieces on recreational RW loads. Meet the minimum skill levelBefore jumpers participate in a skydive that involves piece turning, they should meet the requirements for a USPA A license, which means that they can do individual 360-degree turns, dock on another skydiver, maintain eye contact, track, wave off, and pull. In addition, jumpers should be able to dock on small formations such as a 4-way Star. Start with partial turnsNewer jumpers should start with partial turns (180 degrees or less) on small formations. Here is a fun drill. Build a 4-way Open Accordion, break it in the middle, turn the two pieces 180 degrees and re-dock. This puts the jumpers who were on the inside on the outside, and vice versa. In this drill, think more about “trading places” with your piece partner than about turning the piece. The piece will automatically rotate if you move to the slot vacated by your piece partner. As you move, try to help place your piece partner in the spot you just vacated, keeping your piece level with the other piece as you do. Repeat the process to place yourselves back in your original slots then repeat the drill until breakoff. Move on to 360-degree turnsOnce you can do drills like the one described above, you are ready to move on to 360-degree turns on small formations. A good drill for this is the Zig Zag – Marquis 4-way block. A “block” is a two-formation set in which jumpers build the first formation, split into pieces, rotate the pieces then reconnect them to form the second formation. In competition, experienced teams speed up their turns by rotating the end of one piece over the end of the other piece – in essence, reducing a 360-degree turn to 270 degrees or even less. But in this article, we only discuss flat turns because they normally work best on recreational loads where the objective is not speed but smooth level turns. In the Zig Zag – Marquis block shown above: To start the turn, Jumpers A and B break grips and turn approximately 90 degrees to the right and stop, keeping each other in view over their left shoulder (helps them stay close and level). While this is happening, Jumpers C and D stay put except to extend their arms to let Jumpers A and B move. Once Jumpers A and B have moved, Jumpers C and D “trade places”, keeping each other in sight over their left shoulder as they move. When their legs almost touch, they stop, look over the other shoulder (called a “head switch”) and place Jumpers A and B together in the Marquis. While Jumpers C and D are finishing their turns, A and B also do a “head switch” and keep each other in view and on level while they are placed together. All jumpers should help keep the pieces level throughout the turn. Notes: To be safe while they trade places, Jumpers C and D do not move directly at each other, but slightly offset so that their legs do not collide. Also if they focus on “trading places” rather than spinning their partners around, the pieces are more likely to stay close.The same concepts used for the Zig Zag – Marquis example above can be applied to turning pieces in larger formations. Consider the following example. In the 9-way example above: Jumper A turns approximately 90 degrees to the right and stops, keeping the other pieces in view over his left shoulder (helps him stay level and close). Jumper B moves into the space cleared by Jumper A. At the same time, Jumper C moves into the space vacated by Jumper B. As soon as Jumper A feels the piece rotating, he looks over his right shoulder for the other pieces and stays level with them as the turn finishes. As the turn finishes, Jumpers B and C place Jumper A back into his original slot. All jumpers should help keep the pieces level throughout the turn.Note: Everybody’s initial moves should create enough momentum to keep the piece rotating. If it starts rotating too fast, Jumpers B and C can lower their right knee temporarily to put on the brakes. Similarly, if the piece stops rotating too soon, they can lower their left knee until it starts moving again. Rotate pieces on their center pointsTo keep the pieces close throughout the turn, each jumper must help the piece rotate on its center point. Jumpers in each piece should watch the other piece over one shoulder as the turn starts, then “head switch” and watch it come back into view over the other shoulder as the turn completes. This helps keep the pieces close and on level and emphasizes the following point: If you keep your target in sight, you will be more likely to fly to it. Get the right gripsIn the dirt dive, jumpers should practice the grips they will be taking in the air. This way they won’t be fumbling around for grips when the piece starts turning. Also a grip should not hinder a piece partner’s ability to fly. This is especially true of leg grips. Do not grip at or below the knee because this hinders your piece partner’s ability to move his leg. Instead, grip as high as you can on the outside of his thigh so that when he moves his leg your grip doesn’t move much at all. Tip! High, outside leg grips also help people with short arm spans to fly when they have Sidebody grips. Sidebody grips consist of an arm and a leg grip on the side of your piece partner. It is much easier to fly if your arms aren’t all stretched out. Slow is FastIf the pieces drift apart and get on different levels during a turn, jumpers should not try to make up the distance too quickly. They should get the pieces level first then slowly make up the horizontal distance. Slamming the pieces together in a rush can possibly injure somebody or even cause a funnel. At the very least, it creates a wave throughout the formation that must be dealt with before jumpers break for the next point. If jumpers break before the formation settles down, they will more than likely end up on different levels again. It actually takes less time to get the pieces level and fly them smoothly back together than it does to slam them together then have to deal with an unstable formation. As often is the case, slow is fast. Give it timeLike any skydiving technique, learning to turn pieces effectively takes time. Don’t expect to run straight from your A license exam to jumping on the hot RW loads. Practice on small formations first. Do some 4-way; there is no better training tool for learning how to turn pieces. With practice, you’ll learn to anticipate your moves and to work with other jumpers in the piece. Piece turning is definitely a group effort and when everybody is working together, it feels like the piece has eyes and a mind of its own as it does a smooth, quick and controlled 360-degree rotation then stops on a dime and makes a perfect re-dock on the other pieces!

-

Canopy Relative Work (CRW) may be described as the intentional maneuvering of two or more open parachute canopies in close proximity to, or contact with one another during descent. The most basic maneuver in CRW is the hooking up of two canopies, one below the other. This formation, known as a "stack" or "plane"(the difference between a stack and a plane is the grip on the parachute), is the most common maneuver in CRW. There are two major categories of CRW formations: Vertical formations : Canopies are either stacked or planed one beneath the other. All grips should be on the center cell. Off-set formations : one or more docks and grips are on end-cells. These formations include diamonds, boxes and stair-steps. USPA BSRs recommends a beginner should have the following qualifications before engaging in CRW: At least 20 jumps on a ram-air canopy. Thorough knowledge of canopy flight characteristics, to include riser maneuvers and an understanding of relative compatibility of various canopies. Demonstrate accuracy capability of consistently landing within five meters of a target. Initial training would be conducted with two jumpers - the beginner and an Instructor experienced in CRW. The instructions should include lessons in basic docking and break-off procedures as well as emergency procedures. USPA BSRs has the following recommendations on equipment:The following items are essential for safely doing CRW: hook knife -- necessary for resolving entanglements ankle protection -- adequate socks prevent abrasion from canopy lines. If boots are used, cover any exposed metal hooks short bridle cords -- short, single attachment point bridlecords are essential to reduce the danger of entanglement. Retracting bridle pilot chute systems are desirable cross connectors -- are essential for building planes. These should be connected between front and rear risers only. The following items are strongly recommended for safely doing CRW: altimeter -- provides altitude information for dock, abort and entanglement decisions protective headgear -- must allow adequate hearing capability for voice commands, in addition to collision protection soft toggles -- provide less possibility of entanglement than hard toggles and better flight control trim tabs (go toggles) -- helpful for equalizing decent ratesand increasing control envelope cell crossporting (two rows) -- is recommended (when doneper manufacturer's specs) to minimize the likelihood of canopy collapse cascades -- recommended to be removed from the two centerA lines.

-

Whether you jump at a large dropzone or a small one, you’ve probably shared a ride to altitude with a wingsuiter. Like all skydivers, wingsuiters should receive a thorough gear check, but a wingsuit also creates unique concerns that a watchful eye can catch. Regardless of experience level, it’s possible to make a mistake while gearing up with a wingsuit – in the same way that its possible for any of us to make a mistake while gearing up for a traditional skydive. This is a situation where your vigilance can save a fellow skydiver’s life. Here are a few recommendations that Flock U has for gear checks: A wingsuit skydiver is a skydiver first and a wingsuiter second – you will need to check his or her rig, chest strap, altimeter, goggles, etc. in the same way that you would with any other skydiver. Make sure that the jumper’s AAD is on (if he or she is jumping with one). Pay particular attention to the jumper’s cutaway and reserve handles. While a wingsuiter’s emergency procedures aren’t any different than a traditional skydiver’s, in some suits, handles can become pulled into or obstructed by the fabric of the suit. That can result in a dangerous surprise if a cutaway or reserve pull becomes necessary. After inspecting the rig, examine the wingsuiter’s arm wings – and in particular, examine the connection between the wing and the jumper’s torso. There’s unfortunately no “one size fits all” rule for arm wing inspection, as different wingsuit designs have different wing configurations. That being the case, there are several general categories of wing/torso connections that each raise their own concerns: Cable Thread Systems. Cable Thread Systems consist of a cutaway-style cable that runs through alternating torso and wing tabs, which keep the wing attached to the torso. By pulling on the cutaway cables, the wingsuiter can release the arms of the suit in an emergency. This design can generally be found in BirdMan brand suits, among others. For a Cable Thread Systesm, look to see if the cables are threaded correctly through the tabs, all the way up. In some cases, they will alternate evenly between wing and torso, but often the cable will intentionally be threaded to skip one or more tabs. Don’t hesitate to ask the wingsuiter if you’re not sure – even experienced wingsuiters may not know the proper configuration for suits that they haven’t flown before, and some wingsuiters have preferences for arranging these tabs that differ from the standard. Make sure the wing cutaway handles are properly secured in a Velcro or tuck-tab housing. Note that there’s often both a front and a rear cable on these systems - so check both, on both wings. Zipper Attachment Systems. Zipper Attachment Systems are found primarily on Tonysuit, Phoenix Fly and S-fly brand suits, though there are many different suit designs on the market that use one form or another of the Zipper Attachment System. These systems generally come in two types: “over the shoulder zippers” and “bottom of wing” zipper attachments. “Over the shoulder zippers” are what their name implies – a zipper that runs over the wingsuiter’s shoulder, which connects the wing to the torso. Generally, in this design, the wing isn’t detached from the torso even in an emergency, and the “over the shoulder” zipper is usually only unzipped if the wingsuiter is removing the suit from his or her rig while on the ground. In these models, there’s generally a Velcro breakaway or other cutaway system or a safety sleeve (described below). Look to see if the zipper is attached properly and zipped all the way down. Some wingsuiters will intentionally leave several inches of the zipper unzipped in the back, so ask before correcting a slightly unzipped wing! If the over the shoulder zipper design includes a Velcro breakaway system, check to make sure the Velcro “sandwich” is holding the top and bottom of the wing together and that the Velcro isn’t bunched or pinched – these gaps can widen when the wing encounters the relative wind. Newer Tonysuits brand model have a “safety sleeve” – a ZP liner – that allows the armwing to silde up the jumper’s arm, permitting the wingsuiter to reach canopy controls in an emergency. As a result, there’s no arm wing cutaway system to inspect. When looking at these suits, make sure that the arm zipper – the zipper that runs from the jumper’s shoulder to his or her wrist – is fully zipped. There will generally be a snap or tuck tab on the bottom of the wing; check to see if they are properly stowed. While inspecting the arm wing, check the wingsuiter’s wrist-mount altimeter (if he or she is jumping with one). Make sure that the jumper can release his or her wings without undoing the wrist-mount (which can happen, for example, if the wrist-mount is put on after the arm wing is zipped up in wingsuit designs with a thumb loop). This is a dangerous and easily avoidable method of losing a wrist-mount altimeter! Check to make sure the wingsuiter’s legstraps are on. Leg straps can be missed by wingsuiters while gearing up, as the suits tends to restrict motion and prevent the jumper from seeing his or her legstraps. Even highly experienced wingsuiters have admitted to momentarily forgetting leg straps while gearing up. When using a wingsuit, visual inspection is insufficient to make sure that the leg straps are on – the wingsuit can deceptively pull the strap against the leg, making it appear that the strap is on. Ask the wingsuiter to shrug – the jumper should feel the resistance in the harness created by tightly worn leg straps. Alternately, you can lift the bottom of the wingsuiter’s rig (in other words, under the pilot chute). If the rig moves more than a couple of inches, it’s not secure enough. Each leg of a Tonysuits brand wingsuits also has a leg zipper pull up system, which is basically a bridle that connects to the leg wing zipper. The bridle is stowed against the leg by Velcro or tuck tabs. Also incorporated in this design is a pair of magnets that keep the bottom of the wing together. These magnets must go over the zip pull ups. If they are under the zip pull up, they may jam under canopy. Are the wingsuiter’s booties on? Particularly when the wingsuiter is using a borrowed or rental suit, booties may be ill-fitting. Badly fitted and poorly positioned booties can result in a lost bootie, which can make for an incredibly difficult flight and dangerous canopy deployment. Check to make sure the bootie is on, and straight. Help to make this year a safer year for skydiving by looking out for your fellow jumpers. Making it a habit to look at others’ gear can only result in positive results. Save someone’s life this year - it could be yours! A free, downloadable wingsuit pincheck file can be found on our site at www.flockuniversity.org. This pincheck guide is perfect for printing for Safety Day or for putting on the wall near manifest. Thanks to Jeff Donahue and Andreea Olea for their help in this article. All photos courtesy DSE.

-